Release Date: 19 May 2010

Release Date: 19 May 2010

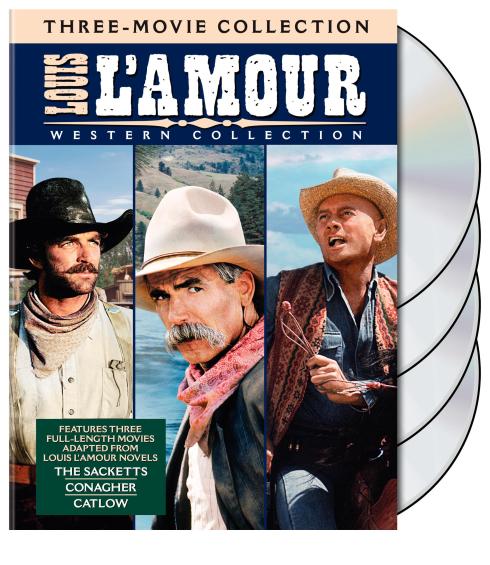

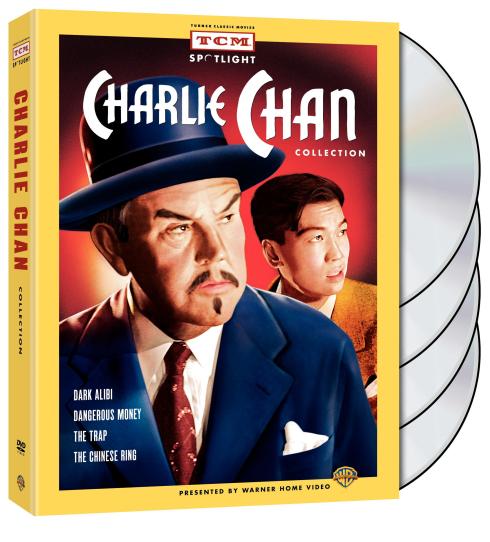

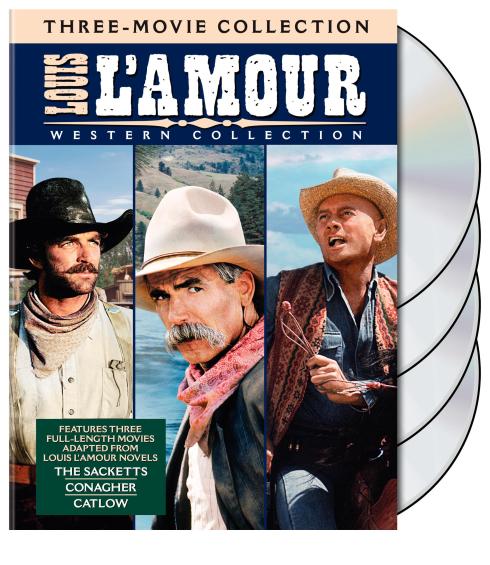

Louis L’Amour (1908-1988) is still the most successful western writer of all time. His prolific output of over ninety novels and six short story collections continue to sell and remain distinctly popular with fans of the genre. Naturally his work was called upon for adaptation on the big and small screen, and this 4-disc DVD set brings together three distinctive westerns: Catlow (1971) starring Yul Brynner, The Sacketts (1979) featuring Sam Elliot, Tom Selleck and Glen Ford, and Conagher (1991) starring Sam Elliot and Katherine Ross.

Buy the The Louis L’Amour Western Collection here .

.

Catlow (MGM, dir: Sam Wanamaker, 1971)

starring Yul Brynner, Richard Crenna and Leonard Nimoy.

A lively performance from the legendary Yul Brynner is the highlight of this pacy, comic western. He plays gunslinging outlaw Catlow, whose attempts to escape the law are thwarted by the determined yet dignified Sheriff Cowan, played by Richard Crenna. The chase kicks off in Apache country, where sniping bullets are accompanied by arrows, and leads Catlow’s posse over the border to Mexico where they attempt an ambitious gold robbery. Cowan gets his hands on Catlow every once in a while, only to be given the slip by his wily, charismatic adversary. But it’s not only Cowan who’s after him; a mysterious hit man is also on his tail, played by none other than Leonard Nimoy.

Yul Brynner was made famous by the exotic, brooding persona that was developed through films such as The King and I and Anastasia. He of course made a name for himself in Westerns through his role in The Magnificent Seven, and Catlow was made only a couple of years before that mysterious persona was used to brilliant effect in the unnerving sci-fi western Westworld. In Catlow he plays against his usual persona with an upbeat comic performance. He’s a man-of-the-world, quick-witted, sly and charismatic. Brynner’s trademark Russian accent and distinctive look almost feel out of place against the dusty surroundings of the Mexican border, but add an appealing mystery to his character.

Since we are in the western world of Louis L’Amour, the film is pleasingly loaded with traditions of the genre, such as gunfights, stagecoach heists and the requisite saloon bathtub sequence. Yet while this is certainly familiar territory, the film distinguishes itself through its breezy tone and easy blending of comic drama with action. Brynner and Crenna as the outlaw and sheriff create a double act, enjoyably playing off each other in their game of cat-and-mouse, and Nimoy is totally convincing as the tough, mysterious hit man. One particularly extraordinary sequence sees Brynner fist-fighting a nude Leonard Nimmoy. It’s as though Women in Love was relocated to the old West.

Made in 1971, Catlow was one of the final westerns with its roots firmly in the tradition of the classic studio-era western. In 1969 The Wild Bunch had already kick-started a tougher brand of western that would lead to a more self-conscious expression of the genre. This meant stronger violence (The Last of the Hard Men), political agendas (Soldier Blue, Little Big Man), elegiac farewells to old Hollywood (The Shootist), satires (The Life and Times of Judge Roy Hill) and twists on the genre (Westworld). Catlow, then, is an unselfconscious western that sticks to its guns and delivers a concise, star-driven and entertaining action picture.

Extra Features: Theatrical Trailer.

The Sacketts (NBC, dir: Robert Totten, 1979)

starring Tom Selleck, Sam Elliot, Jeff Osterhage and Glenn Ford.

The Sacketts is absolutely worth its three-hour running time. An epic adaptation of L’Armour’s The Daybreakers and Sacketts, it tells the story of the Sackett brothers and their journey from cattle drivers to lawmen. Played with typical gravity by Sam Elliot, Tell Sackett is now a hardened, nomadic drifter, whose wanderings lead him on a quest for gold. He hasn’t seen his other two brothers in a decade, and Orrin (Tom Selleck) and Ty (Jeff Osterhage) have since become cattle drivers under the watch of their world-weary boss, played by Glenn Ford. Orrin is a brave, well-liked and noble man that his younger brother Ty looks up to, so much so that when he settles in New Mexico he earns himself a tin star.

The Sacketts is filled with strong performances. We witness Tom Selleck here in his pre-Magnum days and it’s easy to see how he became such a major TV star, giving his character a kind of quiet charisma. He also makes a very convincing cowboy and surely the success of The Sacketts was a major reason why Selleck has continued a sideline in TV westerns throughout his career.

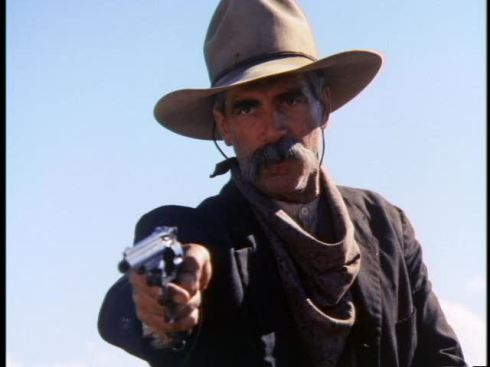

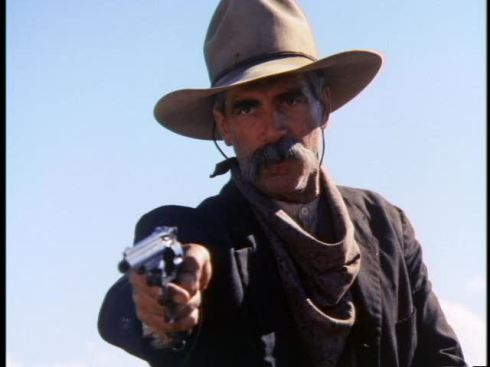

Sam Elliot is perhaps the definitive on-screen cowboy of the modern age. He has forged a career based upon his wise, low-talking, moustachioed western persona, and even in these times when westerns have remained out of the mainstream he continued on with his on-screen character, turning up in the unlikeliest of places (the bowling alley of The Big Lebowski or the fantasy world of The Golden Compass). Here Elliot’s performance is dark, brooding and dangerous. A nomad wandering through mountainous plains, he has become estranged from his family and is now a withdrawn and troubled man. He talks scarcely, yet when he does he reveals himself to be tough, mean, yet fair.

Glenn Ford is part of the old guard of the Hollywood western, having starred in such classics as 3:10 to Yuma, and here you are reminded at what a powerful and meticulous actor he was. A few striking close-ups convey conflicting emotions all at once. He can convey both toughness and weakness at the same time.

The Sacketts is a film that offers up all the pleasures of the western in one place, from the locales: small towns, big vistas, banks, saloons, jailhouses, hotels, gold-riddled mountains; to the plot and themes: cattle-ranching, small-town politics, familial drama, evil posses, and tense shoot-outs; to the authentic performances: the trio of Tom Selleck, Sam Elliot and Glenn Ford, as well as the handful of character actors (including genre veteran Ben Johnson. It’s a film that galvanises the western genre, that defies its running time and which deserves to be seen more often.

It was originally made for television but the scope of the writing and the authenticity of the production design means that it certainly works as a big screen experience. The combination of the tight, varied, suspenseful plotting and the strong performances carry you easily through the film and it certainly earns its three-hour running time.

Extra Features: None.

Conagher (TNT, dir: Reynaldo Villalobos, 1991)

starring Sam Elliot and Katherine Ross.

In contrast to The Sacketts, Conagher is a more intimate drama about homesteader Evie Teale (Katherine Ross) who is forced to look after her children alone when her husband never returns from his journey to a distant town. Her home soon becomes used as a temporary rest point for the new stagecoach and there she comes in contact with a lonely drifter, Conagher, played by Sam Elliot.

As in The Sacketts Elliot’s character is tough and uncompromising, but here he proves also be particularly sensitive. While on the one hand being a dangerous-but-moral gunfighter, he is also struck by a deep sense of loneliness on his travels. He is clearly taken by Evie Teale, whose resilience he admires. Indeed at one point she and her children successfully fight off Indians who attack her homestead. Conagher also has his own problems – a no-good posse are on his tail, leading to a particularly suspenseful game of cat-and-mouse up the side of a rocky cliff, as well as tense gunfights with distant snipers.

Interestingly both Sam Elliot and Katherine Ross share a writing credit on this made-for-TV movie and Elliot was also a co-producer, suggesting that he was a driving force in bringing it to the screen. And although it is a Sam Elliot vehicle Katherine Ross’s is fortunately given enough screen time to develop her character of a resourceful woman in the male-dominated West. Female characters are too-rarely the focus of this often-macho genre and Conagher is a welcome exception. Fans of The Graduate would also be interested in seeing Ross give a strong, low-key performance.

Extra Features: None.

About the Transfers

Catlow looks strong with a transfer that convincingly translates a 70s-era print, maintaining good colours in the brighter sequences, strong detail, and conveying the appropriate atmosphere of the darker sequences. It’s important to note that both The Sacketts and Conagher were made for TV broadcast, so are both are presented in their original 4:3 aspect ratio. The Sacketts contains a great amount of vivid imagery, colour and detail and the print has been cleaned up. Due to its lengthy running time, The Sacketts is spread over two discs. Although the most recent film in the set, the image of Conagher is perhaps the weakest, most noticeably in the darker sequences. While it is a little soft throughout, presumably due to the nature of its TV-broadcast origins, the image is strongest in the brightly-lit, outdoor sequences. However I expect that this image reflects how the film would have been seen on its original broadcast.

Conclusion

These three Westerns are distinctly different from each other but provide interesting and entertaining variations of the western and of L’Amours work, from the light comedy of Catlow, to the epic scope of The Sacketts and the intimacy of Conagher. These would be highly recommended to those interested in L’Amour or in post-classical westerns more generally, but also to fans of its stars: Sam Elliot, Tom Selleck, Yul Brynner and Glenn Ford. While an extra feature giving some context to L’Amour and his work would have been appreciated, ultimately all three films really do entertain. At the price it’s a bit of a bargain for fans of the western.

Buy the The Louis L’Amour Western Collection here

Leonard Nimmoy in Catlow (1971)

Release Date: 19 May 2010

Release Date: 19 May 2010

5 Reasons Why 3D Really Does Not Work

January 23, 2010 in Art, Film Criticism, Film History | Tags: 3D, commentary, editorial, Film History | 16 comments

I’ve received a lot of emails on my post about Why 3D Does Not Work. Many agree, but some others seem to have problems with it.

For those left scratching their heads, here are five simple points:

In 3D individual, isolated spectacles are most effective, for example a bubble leaving the screen and heading towards you, a fish swimming out from the ocean or a secret passageway extending deep into the screen.

3D is most effective as a novelty, not as a sustained visual system throughout a feature film. And there has not yet been a film to prove otherwise.

Photograph (US, J. R. Eyerman, 1952) of an audience at Bwana Devil. Originally published in Life Magazine, hosted by and co. of Google.